It’s been a long hiatus from this blog for a number of reasons (mostly depression-related), but hopefully I’ll be back for a bit now. And how or when better to restart it than today, by marking international Bi Visibility Day?

About two years ago, I partook of some Netflix binges – rewatching all of Buffy and powering through the whole of The L Word were just too irresistible. Although I can’t deny I hugely enjoyed both of these binges, there was something I just couldn’t get past – the way bisexuality was treated in both. They inspired me to start writing a blog about bi-erasure and biphobic tropes on screen over time, but things got in the way, and it was never finished.

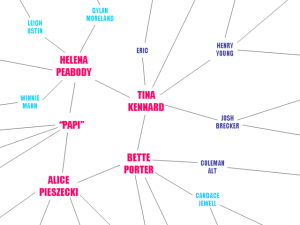

Here’s what Bi TVisibility could look like!

It’s never too late, though! So let’s begin.

[BEWARE – SPOILERS FOR MANY TV PROGRAMMES!]

The year is 1997, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer has hit our screens. (I was only 6, so of course I wasn’t watching it then. But for reasons which will become clear, I feel hugely influenced by this programme, so indulge me.) We have a ground-breaking strong female lead, fighting evil and generally being awesome. And she has two best friends, one male and one female. Let’s focus on them for a second…

It’s made very clear from the start that Willow has been crushing on Xander for a long time. It’s also apparent after not long that it’s not requited. And – remember this – Willow is devastated when it’s finally drummed home.

Fortunately for her, she moves on. She moves on to… Oz. It’s very obvious that their chemistry is strong, and I don’t think the depth of her feelings for him can be denied. Their relationship only falls apart because of one small complication, him needing to take time alone to understand his werewolf identity better. Don’t you just hate it when things like that get in the way?

I highlight these two relationships of Willow’s for an important reason. (Can you see where I’m going with this?) After Oz, her feelings for Tara and, later, Kennedy (both women) are just as strong as we’ve seen her experience previously, but something seems to have changed. We hear her say on several occasions that she’s ‘gay now.’

Look. You made Willow cry now.

Now, let’s clear something up before we go any further. Everyone, 100%, without any exception, has the complete right to decide for themselves how they are defined, in every area of self-definition, and that goes for fictional characters too. If Willow says she’s gay, then within the canon of the Buffyverse, she’s gay. What I take issue with is the fact that this was the way her characterisation was dealt with. It was Joss Whedon and his team who put those words in her mouth. This is the same Joss Whedon who, when interviewed in 2002 about why Willow has a relationship with Kennedy after Tara dies, said ‘We can’t have Willow say, ‘Oh, cured now, I can go back to cock!’ Willow is not going to be straddling that particular fence.’ What particular fence might that be? Not bisexuality, surely?

I’ve given a lot of time here to one TV programme, but there is a reason for it. I don’t remember much of Buffy from the first time watching it, because I was in my early teens, or possibly even younger, and I only ever really watched it when my older brother did. It’s a bit… adult-themed. I definitely didn’t remember the details I’ve described above. The only thing that really stood out to me was Willow with Tara – not who she was with before Tara, or after Tara. My childhood brain saw this revolutionary LBGT+ character openly calling herself gay on screen, and processed it in a way which enforced a binary framework. I honestly believe it contributed in a massive way to my own repression of my sexuality.

My childhood brain saw this revolutionary LBGT+ character openly calling herself gay on screen, and processed it in a way which enforced a binary framework.

Now I watch TV programmes with both a [mostly] conscious adult mind and an understanding of my own space within the LGBT+ community, and I notice things which upset me. There are certain patterns to how bisexuality is treated (or often isn’t treated) on screen which I find very worrying. You’ve either got the complete erasure of bisexuality as a real identity, or the use of bisexuality to portray a character negatively in some way.

So, first, programmes where a character could quite conceivably be identified as bi according to how they are portrayed on screen, but the writers shy away from ever using the ‘b’ word. We’ve already seen Willow in Buffy more than 15 years ago, but it’s still happening today. Let’s look at Orange Is The New Black, which is pretty much at modern cult status. In many ways, it deserves this. It provides a lot of social commentary about race, power and humanity (though I appreciate the concerns many people of colour have expressed around its evolution into trauma porn for white viewers, and I’m grateful to have had these lived experience analyses drawn to my attention). It even tackles trans* issues front on (again, with its own caveats).

What I (and many other people) really dislike is the programme’s presentation of bisexuality, though. Piper describes her sexuality beautifully, saying ‘I like hot girls. I like hot guys. I like hot people’, but you’d think from watching the show that the word ‘bisexual’ itself is taboo or a swearword. The word ‘bi’ is only used once, in a tone of voice which dismisses the concept, but there are no similar qualms about calling her a lesbian, an ‘ex-lesbian’, or ‘gay for the stay’, depending on the scenario and her relationship of the moment. Why does it shy from bisexuality? I’m all for fluidity and embracing a spectrum, but there are millions of people across the world who choose to use the bisexual label proudly, and who, like me, have most likely at some point felt liberated realising that there are others like them. Would it be so difficult to give them someone on screen to identify with? Someone that other people can see and use to come to accept that it’s a genuine orientation too?

Would it be so difficult to give bi people someone on screen to identify with?

Then you’ve got the programmes where the concept of bisexuality is applied to a character to highlight a particularly negative character trait or an unpleasant action of theirs. This one’s a lot more varied and subtle, and isn’t so easily spotted unless you’ve started noticing the tropes. For example, I’ve recently been watching Jane the Virgin and Orphan Black, and there’s a striking parallel between them when it comes to the use of bisexuality.

In Jane the Virgin, we meet Rose, who has a bit of a complicated life – she’s torn up about the fact that she’s sleeping with (and apparently in love with) her husband’s daughter. Yeah. When the series began, my initial reaction was, ‘oh look, another bisexual character who’s being portrayed as unfaithful, promiscuous and confused about her sexuality.’ All common tropes, by the way.

Rose (right), with her husband and her lover. Oy.

But it gets much worse. She turns out to be the international drug lord whom the police have been searching for throughout the first series, and a lesbian, and she only married him as a cover so she could hide an illegal plastic surgery ring changing the faces of criminals under his hotel. I know, it’s all intentionally over exaggerated, ridiculous and far-fetched, but let’s set that aside for a moment. The only character in this programme who demonstrates any form of non-binary sexuality turns out only to be doing it in order to manipulate and deceive those around her.

I could just be reading too much into it, so let’s turn to Orphan Black, a programme with three core LGBT+ characters who are each bad-ass on their own way. There’s Cosima, the super genius lesbian evolutionary development scientist who does everything lab-related to help her clone-sisters (and one clone-brother). Then there’s Felix, the gay ever-present voice of reason and mediator whenever shit starts to hit the fan.

And then we have Delphine, Cosima’s on-off girlfriend and personal monitor in the clone experiment/the eventual director of the super evil corporation which stabs all the clone-sisters in the back and other body parts on a regular basis/eventual eventual renegade fighting on behalf of the clone-sisters. (Are you following that?) And, you guessed it, she’s bisexual. When she first starts to befriend Cosima, it’s at the behest of the man who’s her boss (and apparently also the person she’s sleeping with). Cosima falls for her, so Delphine ‘does whatever it takes,’ and they become a thing – and all the while Delphine is spying on her and reporting back.

As the storyline currently stands (at the end of series four), Delphine actually seems to be in love with Cosima and helps to save her life. The overarching theme throughout the programme, though, is that Delphine is never quite to be trusted, because her loyalties switch regularly and she’s easily controlled. Now, let’s compare that back with Rose in Jane the Virgin. In both, the only character displaying non-binary sexuality (whether genuine or as a guise) is untrustworthy, manipulative and dangerous.

It’s a recurring theme in popular culture that bisexual characters are not to be relied upon as they will ultimately hurt others because of their sexual or romantic expression.

To give benefit of the doubt, I’m sure that neither was consciously written in this way, nor can they be held responsible for the biphobia which pervades much of society. It’s a recurring theme in popular culture, however, that bisexual characters are not to be relied upon as they will ultimately hurt others because of their sexual or romantic expression. And I don’t think the writers of either programme followed that particular trope by accident.

Now, to come full circle, we have The L Word, that wonderful exploration of (mostly) female sexuality that is compulsory viewing for all queer women. If I sound sarcastic, maybe I am a little. It takes the prize with both of the trends described above.

Set, as it is, around the lives of a group of mostly queer women, you might hope it would be interested in unpacking some of the nuances of sexuality beyond the straight-gay binary. Instead, the writers just don’t seem willing to explore any of the bi presenting characters in any kind of positive, affirming way.

Where the first series kicks off, we meet Alice, who self-identifies as bisexual, Tina, who has been with Bette for many years but dated men previously, and Jenny, who has just moved in with her boyfriend. Jenny begins to explore her sexuality through an affair with a woman, ultimately breaking up with her boyfriend, while Tina and Bette clearly have a troubled relationship, which eventually falls apart.

In the third series, we also meet Moira, who begins transitioning to Max within the same series. He is seen in relationships with both men and women, but no one talks much about this sexuality because the focus is on his gender. I’m not going to explore his character in any more depth, because I lack the lived experience to capture the complexity of his gender or sexual identity, but it seems to me that here is another potentially bi character whose sexuality is erased.

What troubles me as the characters and stories develop is firstly what is said within the script to rubbish bisexuality, and secondly the social status of these characters within their universe.

It’s an individual’s choice how they identify, but really, The L Word writers – is it so hard to write Tina as bi?

Towards the beginning, both Jenny and Alice identify as bisexual. It seemed positive in the pilot episode that when one of Alice’s friends asks when she’s going to choose between ‘dick and pussy,’ she responds quickly to this biphobic question. What’s disappointing, then, is how she and Jenny develop over the course of six seasons. Not only do both come to vocally identify as lesbians, but they are also responsible for making some achingly familiar biphobic comments about and to Tina when she dates a man, Henry, after breaking up with Bette. Upon seeing Tina dressed up for a date with Henry, Alice makes a ‘joke’ about now understanding that bisexuality is ‘gross.’ One particularly unpleasant scene in the following series sees Tina being excluded from a basketball team composed of her friends because of it; Jenny accuses her of ‘enjoying all the heterosexual privileges’ because she has a boyfriend, and says that Tina can no longer be part of their group. Interestingly, though, Tina insists that she is ‘still a lesbian’. As in Buffy, if that’s how she identifies, then we must accept her self-definition, but why could the writers not consider letting her use the ‘B’ word instead? And why do the writers stop challenging biphobia within the dialogue as they have Alice do in the pilot?

This scene with Tina takes me smoothly to the second point – how the characters displaying non-binary traits are seen within the social group and portrayed to the audience. While Tina is dating a man, she is almost completely shunned by her social group because they see her as betraying the lesbian world. The implication that she is only doing it in order to spite Bette would barely even count as subtext. Yet another instance of bisexuality being used as a tool to portray duplicity in a character. When it comes to the social statuses of Jenny and Alice, I think the writing is more subtle, but both demonstrate the use of tired tropes too. Both are depicted as unstable, suffering from severe mental illness explicitly linked to their conflicted sexual identity, and neither really receives the support they need from those around them when they are at their worst. I doubt it’s any coincidence that the chronology of both of their storylines place their new lesbian identities as things acquired after the lack of support they receive from their friends.

So, there we go. According to The L Word, bisexuality is merely a stepping stone to homosexuality, and it implies that people who identify as or act bisexual haven’t yet earned their place in the queer world. The programme deftly manages simultaneously to erase and attack the bisexual identity.

I suppose we shouldn’t be all that surprised, though – bi-erasure is right there in the programme’s name.

This lengthy overview of bisexuality on screen is by no means comprehensive, and there are other excellent blogs examining the issue. There are plenty of other programmes I could have brought in, from Queer as Folk to Glee, but I wanted to limit myself. (And, also, Kurt’s ‘bisexual is a lie gay guys tell in high school to hold hands with girls in the corridor so they can feel normal for a change’ line makes me too angry for coherent sentences.) I think it’s important to note, though, that all of the programmes I’ve looked at are pretty progressive in many ways, exploring issues like sexuality, gender non-conformity, race, minority communities and power, and would all score relatively well on the Bechdel test. So why are they still falling so short on bisexuality?

The more it’s seen, the more it becomes normalised in society.

Now, I’m sure there’ll be people who think ‘so what if you don’t get the token positive bisexual character you want in TV? It’s not like it reflects real life or anything.’ But that’s just it. It should, and it needs to. It’s not all that long ago that queer culture and identities started to be represented on screen in the first place, even though they’ve always been there. Now it’s becoming more common, and more accepted, to see same sex couples on mainstream TV or in films, which is fantastic. The more it’s seen, the more it becomes normalised in society. Being gay is far more accepted today in Western countries than it was not all that long ago, and I have no doubt that pop culture helps with that, because the law rarely leaves the ivory towers. It’s time for bisexuality to get that same recognition and acceptance, in both the straight and queer worlds.

For me, the real question is this. Would the on-screen depictions of bisexuality in TV programmes today be sufficiently visible and positive to allow a child version of myself to build a framework of sexuality which included bisexuality as equally valid? Sadly, I think the answer is a resounding no, and until the answer is ‘yes,’ I will keep pushing for our bi voices to be heard and our bi faces to be seen.

If you have any comments, and particularly any recommendations for TV programmes in which bi characters are given a decent treatment, I’d BI very glad to read them below!